The Tenement, a Territory and an Unexpected Oasis

When Brutalist Social Housing Meets a Collective Culture

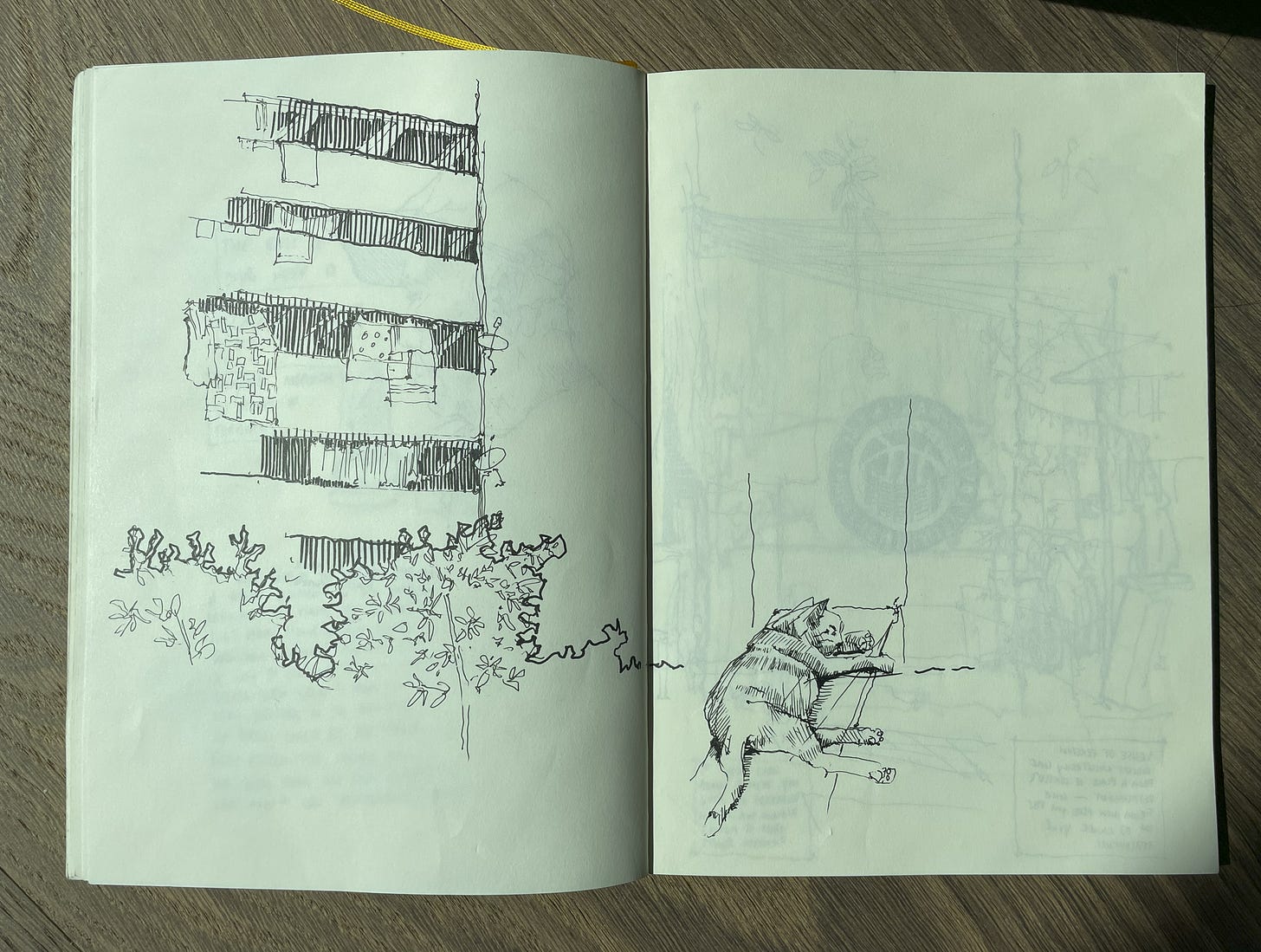

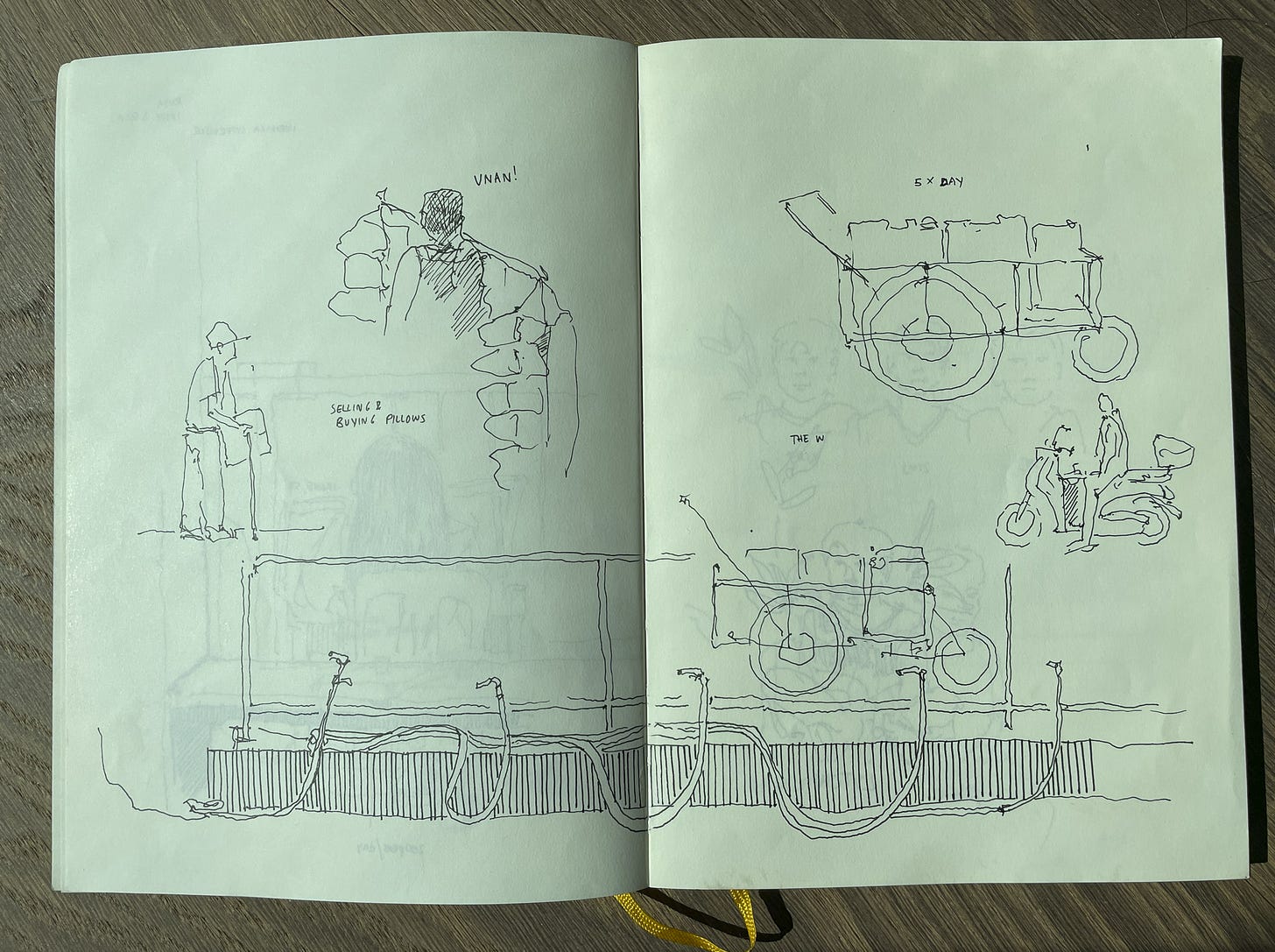

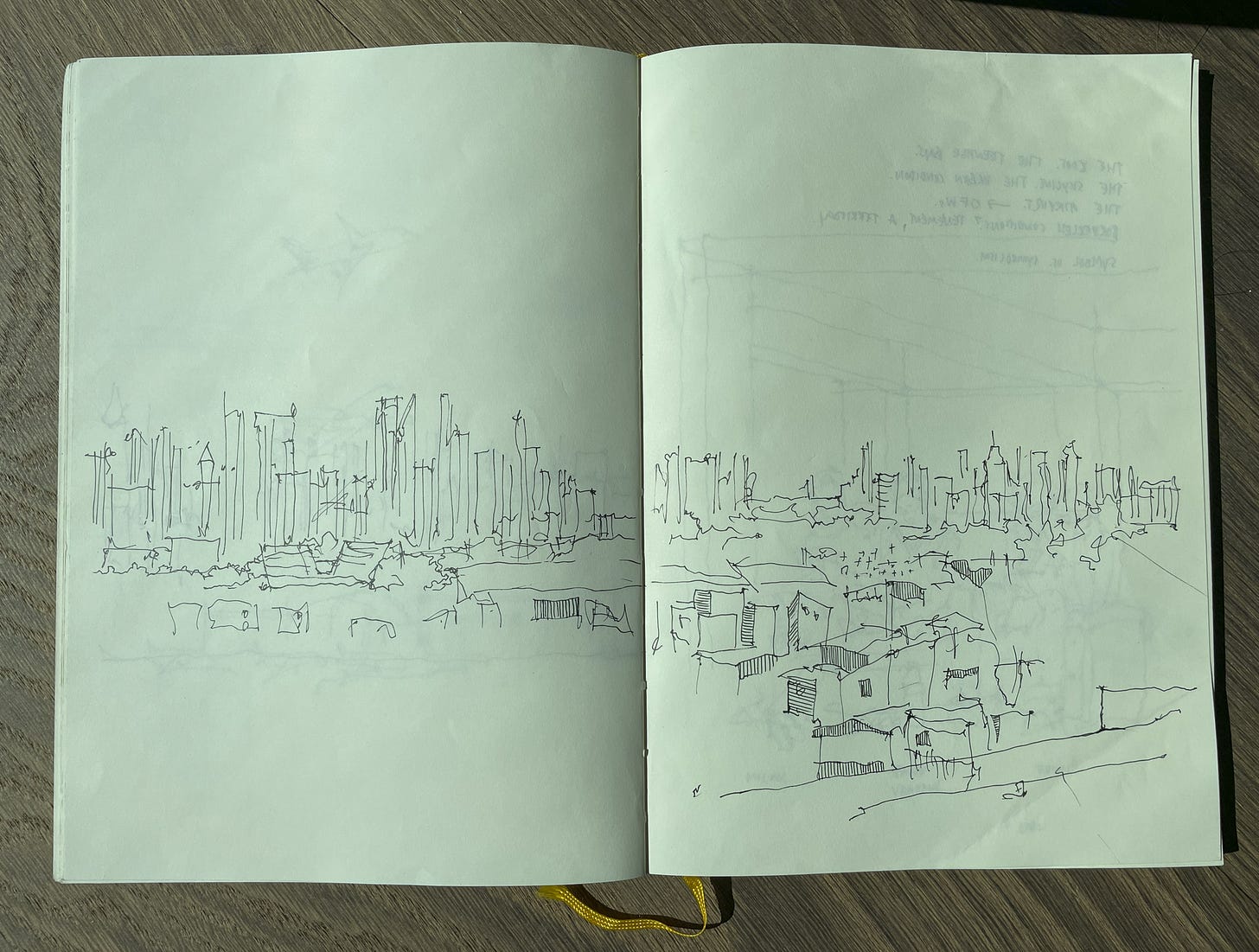

This piece was co-authored with my brother, Gabriel Schmid. As siblings, both immersed in the world of architecture, we like to think about the relationships between space and community, and have developed an appreciation for the Western Bicutan Tenement. Gabriel grounded his architectural thesis in this social housing project, while I’ve spent significant time simply being there—observing, meeting, and drawing. Through our combined perspectives, shaped by architectural analysis and lived experience, we explore how this building reveals its meaning not just in form, but in the lives it supports. All visuals were taken by either one of us. Art by Gab. Sketches by Rhea.

The Manila heat can be relentless. The air hangs heavy with humidity and smog. We drive toward a large concrete structure, passing through a sea of one- to two-story buildings. Its exterior is battered and worn. The building resembles a ship caught in rough waters: massive, weathered, and seemingly forgotten. As we drive along the 150-meter-long, seven-story-high wall on one side, we pass a row of small food stalls crowded with people, spilling onto the street, navigating the traffic. We turn the corner and park just outside the entrance to the Tenement.

The Western Bicutan Tenement stands as a unique fixture within Metro Manila's dense and layered urban landscape – a sprawling conurbation of sixteen cities shaped by centuries of colonial rule, waves of rural-to-urban migration, and unchecked privatized development. To understand this building is to recognize how Manila’s urban form reflects 350 years of Spanish colonization, 50 years of American occupation, the devastation of World War II, and successive waves of speculative development with little public oversight. Within this fractured metropolis and its persistent housing crisis, the Tenement offers something remarkable.

Inside, the atmosphere is palpably different from the congestion just beyond its walls. Despite the aging façade, the interior is calm and alive. Paint covers the walls wherever paint rollers could reach, bringing color to the dynamic surfaces. Wide hallways that double as balconies covered with plants, lights, posters, and laundry. Light spills in, and shadows cut through the space into the courtyard. There’s a tree in the middle of the courtyard, perhaps a Dita.

Stepping into the Tenement feels like stepping into another world. As a few kids practice their three-pointers on the basketball court, others rally across a badminton net, and a couple of men sit in the shade, playing chess.

“I’m from the housing project across the street,” one of them says. “It’s not as hot here.” Check.

Built to rehouse 720 families from nearby informal settlements, the Tenement is a postwar housing project that still stands more than six decades after its completion. The concrete mass consists of two long housing bars connected by two ever-buzzing ramps that flank a shared central courtyard. Each 20sqm unit is cross-ventilated, with windows on each end of the room. The ground floor, including the space around the courts, has self-organized into overlapping zones for sports, performance, and play. Even a clinic, a community center, and a chapel emerged from what was once conceived as only housing. The ramps function like vertical highways, while the courtyard provides a central platform for fiestas, congregations, and games. In recent years, the basketball court has gained media attention, serving as a canvas for public art and community expression, most notably a mural honoring Kobe and Gianna Bryant after their passing.

Motorcycles, trolleys, and residents pushing carts with water containers move up and down the inclined ramps. Most residents haul water up to five times a day, as lowered government water pressure prevents it from reaching the upper floors, leaving them no choice but to carry it by hand. One woman in her sixties, lifting a full container with a laugh, chose to focus on the good: “It keeps me really fit.”

Halfway up the ramp system, we glance over to our sides, the tenement sandwiched between framed skies and the court. Above the clouds pass, and below the children dribble balls across the court, as the sound bounces across the space. Manila feels far away, though just on the other side of the walls.

Activity extends along the wide walkways and ramps to the top, which not only serve as circulation but also function as active community and retail spaces, supporting resident-run barbershops, food stalls, internet cafés, and sari-sari stores. All of this exists within the Tenement walls, forming a clearly defined and protected world. From the rooftop, Metro Manila unfolds in every direction. The density surrounding the project is striking. It feels like standing at the edge of a vessel, where the towering skylines of Makati and BGC loom like oncoming waves.

There is much to critique, including government negligence that manifests in the lack of water supply and crumbling infrastructure. And yet, life fills the space, with a sense of pride and dignity deeply connected to the building itself. People are proud to be part of this community, they are proud of the Tenement. They are no strangers to fighting for their rights to be there. In response to an eviction order by the National Housing Authority in 2014, the community rallied, hanging protest posters while standing their ground. They won.

The Tenement is a territory, an unexpected oasis. It feels like the eye of a typhoon too.

Originally managed by the city, the Tenement is now overseen by a homeowners association that coordinates building maintenance, community events, and security. Crucially, many descendants of the original residents still live there, fostering a strong sense of continuity and belonging across generations.

Its success contrasts sharply with similar projects abroad. Take the Robin Hood Gardens designed by Alison and Peter Smithson in 1972 in Poplar, London, for example. By internalizing public space, the Smithsons hoped to promote a sense of shared responsibility and inspire healthy communal living. Unfortunately, their vision never materialized. Poor maintenance and systemic socio-economic inequality undermined their intentions. High crime and vandalism—the very behaviors that the Smithsons believed their architecture would mitigate—directly contributed to its eventual demolition. This highlights how cultural norms/practices/values, location, and community cohesion shape the long-term viability of brutalist social housing, it hardly works in reverse. Architecture cannot shape attitudes, it can encourage or limit what’s already there. The Western Bicutan Tenement stands as a testament to self-determined, community-centric ways core to Filipino culture. The building provides the structure, but it’s up to the community to breathe life into it.

Architecture often aims to create a sense of harmony or unity that is imposed from the outside. Design will always involve a degree of imposition. But if it can shift from being a monolith to becoming part of an ongoing dialogue, it opens the possibility for unity and belonging to emerge naturally, shaped by those who inhabit the space. The challenge lies in finding a balance where design asserts itself with enough clarity to guide, yet with enough humility to allow life to take shape around it. Ironically, in this particular context, a brutalist building, often interpreted as harsh or unfeeling, does exactly that.

This requires intentionally leaving room for organic growth and adaptation. For example, each unit is left to the residents to make their own, allowing for personal tastes to co-exist alongside the rigid concrete. It is not only about producing a finished product, but about creating an opening where community life can take root and evolve. Is the Tenement an example of people leaving their mark in dialogue with architecture?

When the built environment intentionally fragments a people, it is easy to point at the people and fault them for their own fragmentation. However, if we’ve learned anything about Pinoy Pride, it is that it contains a beautifully stubborn and trusting belief that wholeness, that shared something-something, exists, even when the world around looks fragmented and polarized. The residents of the Tenement, given the space to work together, get to practice this belief every day. We see this in how the Tenement community has self-organized, persisted, and created meaning. So, what then is architecture’s role in supporting collective communities within urban contexts?

Architecture shapes space. It shapes how people meet the physical world as it is. At its core, architecture is a protective act, a series of variations on shelter. It keeps us dry. Keeps us warm or cool. Keeps us safe. It keeps out, it keeps in. It offers stability, durability, and a steady presence that supports those nearby, especially those safely within its walls.

Physically and psychologically, it says: Here, you are allowed. Here, you belong. There is space for you and yours.

If social architecture can offer protection without becoming patronizing, then we must be clear-eyed about the forces the most vulnerable are up against. Architecture may not be able to change these conditions, but its physical presence can help buffer against them. In the past, the primary threats were environmental: storms, heat, and rain. Today, the more pressing forces often come from within the systems themselves – failures in governance, systemic neglect, and a long urban history shaped by rupture, inequality, and corruption. These overlapping pressures have produced a fractured metropolis and a housing crisis that has persisted for over a century.

An anomaly within the fragmentation caused by profit-driven housing models that often favor profitable spectacle over social substance, the Tenement affirms every citizen’s right to safe, dignified shelter within a meaningful and connected whole. It offers a quiet critique of systems that separate people from their cities and each other, and instead presents architecture as a form of physical protection, a formal, dignified structure through which local culture and collective experience can take root and grow without unnecessary interference.

This kind of architecture is both resilient and generative: accidental armor, a supportive trellis, and a public platform. It provides shelter and stability while making space for openness and change. Rather than imitating collective living, it enables and strengthens it, meeting essential human needs for security, continuity, and belonging – conditions that allow life not just to survive, but to thrive.

Coming back to this to watch the snippets of life in the videos included, especially moved by the pink/green contrast. Love the comparison with the less successful project in London and reflection on how the people/culture shape how we live in architecture, not vice versa.

“It feels like standing at the edge of a vessel, where the towering skylines of Makati and BGC loom like oncoming waves. At the very top, we see Metro Manila in all its sprawling madness. It feels like being on the bow of a ship, where Makati and BGC look like oncoming waves crashing in the distance.”

Beautifully written! 10/ement